After the liberation of Kherson, the Russians launched a brutal campaign of terror against civilians on the left bank of the Kherson region, which remains under occupation.

In November 2022, 21-year-old Kherson State University student Anya Yeltsova was abducted in the village of Ahaymany. FSB officers stormed her grandmother’s house, conducted a search and interrogations, and eventually brazenly took Anya away in front of her relatives. For over two years now, she has been held in captivity in Crimea, accused of espionage because of her pro-Ukrainian views and love for her homeland.

We spoke with Anya Yeltsova’s family members and relevant officials to find out who might have tipped off the occupiers about her, how she manages to stay in touch with her loved ones, why the Russians are falsely claiming they only detained her a few months ago, and how they forced her to make a false confession.

“Everyone knew she supported Ukraine”

“Grandma was there when they took her,” recalls Anya Yeltsova’s aunt, Svitlana Kushnir. “Anya had gone to visit her grandmother, who is the head of a local school. Russians often came to her, trying to force her to cooperate.”

Her grandmother always refused to collaborate. But that time, they didn’t come for her. Everyone in the house was separated into different rooms and interrogated at length — especially Anya. Her grandmother heard the armed men in balaclavas openly saying that they had been monitoring her granddaughter on social media for a while. They also said they found something on her phone that they didn’t like. The occupiers interpreted it as support for the Ukrainian army.

“Bag over her head. And into the car. That’s how they took Anya,” Svitlana says.

The Russians persecute residents of occupied territories for any expression of patriotism, Ukrainian symbols, and the like. And those like Anya Yeltsova, who openly declare their stance, are targeted even more severely. For many residents of the Kherson region, patriotism has cost them their lives.

“We understood that Anya held pro-Ukrainian views, that she didn’t want to cooperate [with the occupiers],” says Svitlana. “She used social media to ask for help [for the Ukrainian Armed Forces]. When Kherson was liberated, she posted a video saying, ‘Kherson, my dear, you’re home.’ She also wrote that winter was coming and called on people to help our boys with warm gear. So of course, everyone knew she stood with Ukraine.”

On Anya’s social media accounts, patriotic posts can still be found — even poems she wrote from the perspective of a Ukrainian soldier. When she shared them, the student likely had no idea what her pro-Ukrainian stance would cost her, or what the Russians were capable of.

Student resistance

Anya Yeltsova is from the village of Balashove in the Ivanivka district, located on the left bank of the Kherson region, about 80 kilometers from Henichesk. The Russians occupied it immediately after the start of the full-scale invasion.

Her parents are ordinary villagers. Anya stayed in touch with them, but she lived in Kherson, where she was in her final year at Kherson State University and was set to receive a teaching degree. She wanted to become a psychologist and loved to draw.

On March 1, 2022, Russian forces entered Kherson. The city’s residents began organizing rallies against the occupation, openly showing their Ukrainian identity and even blocking the movement of Russian military equipment. Kherson’s resistance inspired the entire country.

In response, the Russians began targeting pro-Ukrainian activists, journalists, politicians, ATO veterans, volunteers, and anyone who could be connected to the resistance movement. One by one, people were taken from their homes to torture chambers, pursued, and intimidated.

Starting in April, as the Ukrainian Armed Forces began liberating villages in the Kherson region, the occupiers ramped up their repressions against patriotic residents, fearing the upcoming counteroffensive. That’s when Russian soldiers came to the dormitory where Anya was living.

“The Russians told the students to either cooperate with them or leave the dorm. How could they possibly cooperate? I can’t imagine it,” says Anya’s aunt, Svitlana, in disbelief.

For the students, showing patriotism meant being heroes of their time. Anya couldn’t act otherwise. Faced with the occupiers’ demands to collaborate, she left the dormitory in Kherson and returned to her home village of Balashove. Later, her grandmother invited her to stay in the village of Ahaymany, also in the Kherson region. Anya agreed and moved in with her.

Who informed on Anya – and why

After the Russians took Anya captive, her grandmother’s health began to deteriorate seriously. She felt deeply guilty for what had happened to her granddaughter.

“At first, just hearing Anya’s name would make her faint — that’s how guilty she felt that they had taken her granddaughter,” says Svitlana. “And then [a few months later], I came across a journalistic investigation claiming that my niece was betrayed by a woman from the same village — a collaborator. This woman was always dissatisfied with something, and during the occupation, she agreed to work with the Russians. Out of revenge toward my mother — who refused to head the local school under occupation — she may have set Anya up.”

The investigation suggests that the person involved in Anya Yeltsova’s abduction could be Halyna Kostenko, the de facto Russian-appointed head of the village of Ahaymany. Early in the occupation, she had reportedly volunteered herself for the role and, having received a level of power she’d never known before, sought to prove her importance.

Kostenko actively cooperated with the occupiers: she settled Russian soldiers in vacant homes, demanded that locals apply for Russian passports, and threatened the parents of young children with deportation to Russia if they did not comply with her demands.

The author of the investigation, citing local residents, claimed that Kostenko was trying to take revenge on Anya’s family for their defiance and to intimidate others, forcing them to cooperate with the enemy.

In November 2024, the Office of the Prosecutor General informed Kostenko that she was under suspicion for collaborationist activities. She faces a sentence of five to ten years in prison with the confiscation of her property.

A year-long search

After Anya’s detention, her parents immediately began searching for her and traveled to Henichesk.

“We went to the military commandant’s office, they just sent us back and forth. Some people said it was ‘not allowed’ for us to know anything, others said no one would tell us where Anya was. They also said it was pointless to file a report,” says the girl’s mother, Oksana*.

A few days after the abduction, Anya managed to call her parents and briefly told them she was fine, saying that she was being fed and wasn’t being mistreated. However, she didn’t reveal where she was.

Relatives of the captive on the Ukrainian-controlled territory contacted the police and all possible official bodies. However, state institutions in Ukraine are physically unable to search for people in occupied territories.

Then, in December 2022, a video with Anya appeared on the Russian propaganda outlet “RIA Novosti,” which was seen by the girl’s relatives and friends, who recognized her. In the video, she is seen looking down, monotonously reciting disconnected phrases.

Both Anya’s aunt and her friends believe that violence was used against her to force her to falsely confess publicly.

“She has bruises under her eyes. And if you zoom in on the video, you can see she’s crying, tears in her eyes. She doesn’t usually look like that,” emphasizes Svitlana.

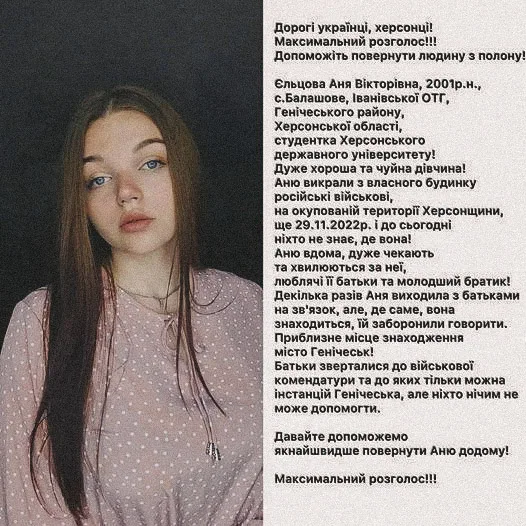

From the very beginning, Anya’s friends and acquaintances raised the alarm and spread her photo along with a message about her disappearance. The entire university community was worried about her fate.

“She was a student at Kherson State University. Her parents haven’t had any information for a month,” wrote the university’s rector, Oleksandr Spivakovskyi.

Instead, the Russians, through their propaganda efforts, promoted rumors that supposedly no one was looking for the student except the rector, and that her disappearance was fabricated.

On some propaganda channels on social media, the occupiers spread posts in which they threatened Anya with up to 20 years in prison, called her a spy, and claimed that she had allegedly passed some information to Ukraine’s intelligence services.

Relatives made every effort to encourage people to join the public search for Anya and continued to reach out wherever they could. By the beginning of 2023, her parents still did not know where their daughter was and believed that the kidnappers were keeping her somewhere in Henichesk.

“I really don’t know how Anya’s mother endured this,” says Svitlana. “She said that in the evening, she would pray and tell me: ‘I’m talking to Anya.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, talking?’ And she replied, ‘I tell her everything will be fine, I know you will come back home.'”

The first letter home

A year had passed since Anya’s abduction when her parents finally received a letter with a Crimean postmark. This was when Anya’s mom and dad first learned what had happened at her grandmother’s house and where Anya had been all this time.

“My daughter wrote that when we first came to Henichesk, she was there,” says Oksana. “And a couple of days later, on December 20, her birthday, they took her to Melitopol. From there, within a month, they sent her to Crimea.”

The girl also wrote that it wasn’t worth coming to see her, as they wouldn’t let her meet her family. Based on the handwriting and writing style, her parents understood that it was definitely Anya. In the letter, she asked her parents to contact her via “Zona Telecom.”

So her parents sent Anya letters, but for some reason, she never received them. This continued for almost two years. Only in August 2024 did a man, who introduced himself as a state-appointed lawyer, contact her parents regarding Anya’s case.

From him, the relatives learned that the student was suspected of espionage and so-called “treason of the homeland,” referring to Russia. For such an accusation, the girl would have to be at least a citizen of the aggressor country. However, it is possible that she was forced to obtain a Russian passport. Later, after the lawyer appeared, Anya herself also reached out.

“She called for the first time. And she couldn’t say much. She said she had lost 10 kilos, and that it was very cold, that there were bars on the window, but no glass,” her relatives recount her words.

Through another person, whom they paid for this as a service, her parents were able to send her personal hygiene items and clothes. However, the so-called prison staff returned the bed linens to them because they weren’t white — allegedly, only white linens were allowed in the detention center.

To all the questions regarding Anya’s case, her parents were told that everything was classified. At least, the relatives understood that the student was being held in one of the detention centers in Crimea.

Then, suddenly, on October 18, 2024, a news report appeared on the Russian propaganda media TASS with a video in which, despite the blurring of the face, Anya could be identified. The story claimed that the Russian FSB had allegedly detained a resident of the Kherson region in Crimea for espionage on behalf of the SBU and that she had allegedly collected and passed information about the location of Russian military forces.

At the end of the video, the courtroom is shown, and it is heard that the girl is being placed under detention for two months while her case is being reviewed in court.

“I don’t understand why they’re lying like this, if she has been with them for two years? But the Russians say it’s only been two months,” the girl’s aunt is outraged. “Maybe the occupiers are trying to scare people in Crimea. Recently, they’ve been publishing a lot of information about someone being caught in Feodosia or Sevastopol. And what’s the point of saying she allegedly passed information to the SBU… We all understand that what they tell her to say, she says. I don’t think she confidently speaks like that on her own. They forced her.”

In the same cell with Anya are other Ukrainian women whom the Russians accuse under the same charge of espionage. Among them is volunteer Iryna Horobtsova, who was abducted by the occupiers in May 2022. Some of the prisoners, including Iryna, have received sentences—decades of imprisonment. All of them are eagerly awaited by their loved ones back home.

“We are waiting for her so much, we miss our dear daughter,” says Anya’s mother.

“Forced to self-incriminate”

Anya Yeltsova’s case contains many elements of a war crime, according to the General Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine.

In particular, law enforcement sees signs of enforced disappearance, which occurred in the presence of witnesses. In November 2022, FSB officers took the girl from her home in front of her relatives, heading in an unknown direction, and then concealed her whereabouts for a long period, completely cutting off her communication with the outside world, violating her right to defense and medical assistance.

An attorney appeared for Anya only after a formal arrest—almost two years of her unlawful detention in complete secrecy. Later, the Russians released a video in which the girl confesses. This practice has become a tradition for them.

“Anya was simply forced to self-incriminate,” explains Yuriy Belyusov, head of the Department for Combating Crimes Committed in Armed Conflict at the Office of the General Prosecutor of Ukraine.

“Over 90% of hostage confessions to alleged crimes are evidence that the person was subjected to torture and cruel treatment. Hostages may self-incriminate or say things that were not actually true. This is almost a 100% confirmation that serious psychological or physical pressure was applied to the individual.”

The appearance of a new video with Anya, almost two years after her disappearance, could have many reasons — including the intention to intimidate Ukrainian civilians in the occupied territories. However, in this case, this motive is considered an additional factor by Yuriy Belyusov.

When the Russians alter the real date of a person’s detention, it is an attempt to conceal the crime of enforced disappearance and unlawful detention. If no information is available about the person, their calculations suggest that it will be difficult to prove that the person was in their custody. In 99% of cases of enforced disappearances, it also involves unlawful criminal prosecution and deprivation of the right to a fair trial.

According to the norms of the European Court of Human Rights and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture, every detained person has the right to defense, medical assistance, and contact with the outside world. The lack of these rights already casts doubt on any verdict in such a case, according to the Office of the General Prosecutor. But the most important thing is to gain access to information about the unlawfully detained person. Here, defense plays a crucial role.

“People detained, as a rule, are charged with various offenses: ‘espionage,’ ‘resistance to the ‘special military operation,’ and other ‘terrorist acts,'” says Yuriy Belyusov. “It is crucial to ensure protection for people in the occupied territories as much as possible. There are several desperate organizations that engage in the judicial process, and it is from them that information can be obtained about what is happening in the case.”

In accordance with international humanitarian law, Anya Yeltsova is a civilian hostage. In Ukraine, her case is being investigated under Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine — violations of the laws and customs of war. Specifically, this concerns the fact of enforced disappearance and unlawful criminal prosecution, as well as the investigation of torture and inhumane treatment.

According to the rules and customs of war outlined in international humanitarian law, civilians are under special protection, and any detentions, involuntary confinement, and judicial processes against civilians are illegal. Russia ignores the norms of international humanitarian law and is systematically unlawfully prosecuting civilians in the occupied territories of Ukraine.

Often, hostages are kept incommunicado for years before formal detention is carried out. After this, long unlawful trials occur, resulting in harsh sentences of many years of imprisonment.

At the end of October 2024, Anya’s parents were able to have a visit with their daughter.

“It was very hard for mom during those two visits,” says Anya’s aunt, Svitlana. “She said she was taking sedatives to avoid crying, but they didn’t help. According to the rules, visits are allowed only twice a month, but it was very expensive for mom to travel, so she used these two days for two consecutive visits. Anya said that this detention center is better than the previous one. But still, mom sends her a lot of medication, painkillers, and sedatives. Of course, Anya can’t say anything. You can see that she’s mentally broken.”

According to relatives, the first so-called court hearing for Anya’s case will take place soon, and for this, she will be taken to Chonhar. During the trial, Anya is prohibited from seeing or communicating with her parents. On February 13, 2025, Russian media reported that Anya was sentenced to 10 years in prison for “espionage.”

*Name changed

The text was prepared in collaboration with The Reckoning Project — a global team of journalists and lawyers focused on documenting, reporting, and collecting evidence for the investigation of war crimes — specifically for Signal to Resist.

Tags: investigation kherson Russia russia ukraine war Ukraine war