We buy only from ‘our own’: how Umerov created a “closed club” of those he purchases weapons from.

Ukrainian weapons manufacturers continue to demand that the state allow them to export despite the war. After all, the government does not purchase all the weapons they are capable of producing.

Anti-Corruption Action Center investigates.

In October 2024, President Zelenskyy promised to purchase all 4 million drones that can be produced in Ukraine. However, this has not happened. Instead, the Ministry of Defense under Rustem Umerov allocated funds only for 2.6 million drones.

Recently, Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated that Ukraine could produce up to 8 million drones annually. However, there is a problem with financing.

Going forward, the situation for Ukrainian weapons manufacturers could become even more critical. This is evidenced by documents obtained by the Anti-Corruption Action Center.

Yes, at the Defense Procurement Agency (DPA), which manages the largest budget for weapons in the country – over 380 billion hryvnias per year – the procurement procedure has significantly changed.

Recently, the DPA has been purchasing weapons only from specific companies that the authorities select manually through decisions made by working groups. The updated procurement procedure at the Agency was approved at the end of May.

Do you produce high-quality, army-tested weapons, offer a good price, have the capacity to manufacture a certain volume, and want to sell to the state? Good luck. Because the Agency will consider your commercial proposal only if it was submitted in response to a request from the DPA itself. If you want to sell, you need to know who to “talk” to and how.

All this happens against the backdrop of constant statements by the head of the DPA, Arsen Zhumadilov, about the transparency of the Agency’s work. He specifically said:

“During conversations with manufacturers and the military, we identified key barriers — non-transparent procedures, difficult access to participation, and lack of dialogue. Therefore, we updated our approaches: we created clear rules, simplified entry, and made the process predictable. This opens opportunities for the market to scale up and allows the state to quickly meet the needs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.”

We are investigating why this happened and why Umerov’s team is abandoning honest (and competitive) procurement rules for weapons in favor of a ‘closed club’ of their own.

A brief background

At the beginning of this year, Arsen Zhumadilov took the position of head of the Defense Procurement Agency (DPA) — initially as acting head, then as the full director. This happened not without controversy: Defense Minister Rustem Umerov made the appointment “bypassing” the supervisory board. In particular, to appoint Zhumadilov, Umerov excluded Taras Chmut and Yuriy Dzhygir from the supervisory board.

Before Zhumadilov’s appointment, the DPA was led by Marina Bezrukova. Her deputy — former head of NABU Artem Sytnyk — was responsible within the Agency for security and anti-corruption issues.

One of the main changes introduced by the previous DPA leadership was the principle that “everyone sees everything.” Weapons manufacturers could send commercial proposals to the DPA without any restrictions. These proposals were immediately visible inside the Agency to several members of the leadership: the Deputy Director for Development and Market Policy, the First Deputy Director, the Deputy Director for Security, and then to the relevant specialized departments.

At that time, the DPA also created conditions under which procurement was open to everyone: there was no need to receive a request from the Agency in order to submit a commercial proposal. At several key stages of the procurement process, the DPA notified potential suppliers about the status of their submitted proposals.

Thus, it was practically impossible to arrange corrupt deals “quietly.”

These were just some of the changes that allowed the Agency in 2024 to significantly reduce the average contract prices compared to 2023: by 15% for 155-mm shells, 23% for 152-mm, and 16% for 125-mm.

The share of intermediaries also decreased significantly. While under transitional contracts signed in 2023, intermediaries accounted for 82% of contract sums, in 2024 this dropped to 12%.

The previous DPA leadership reported on all these changes early this year: the DPA Procurement Procedure that was in effect in 2024.

What’s in the new procurement procedure under Zhumadilov and Umerov

The Anti-Corruption Action Center (ACAC) conducted a comparative analysis between the defense procurement procedures before and after Zhumadilov’s appointment to the Agency.

Since Zhumadilov’s arrival, the procedure has been changed several times. According to our information, the latest updates took place on May 29.

Below, we highlight the key provisions that already not only risk negatively affecting the amount of weapons at the front but also carry enormous corruption risks.

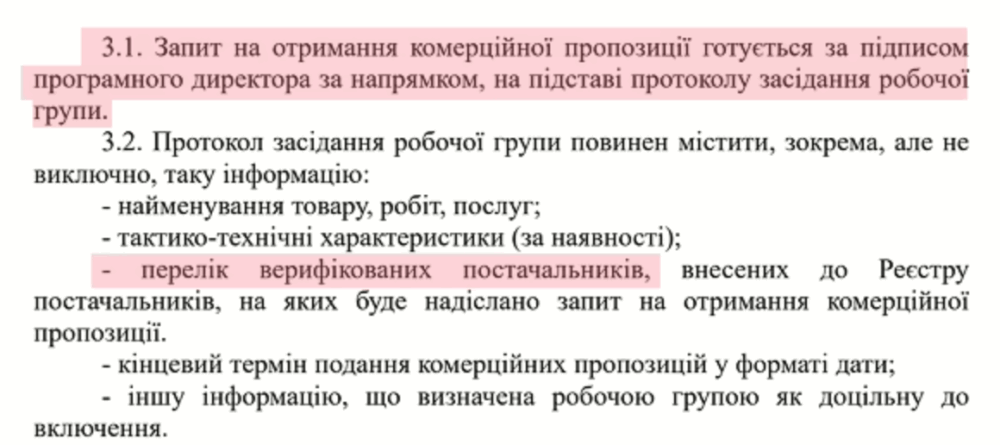

Under the new procurement procedure, only commercial proposals submitted in response to a request from the Agency are considered. In other words, manufacturers and suppliers cannot offer their products to the DPA unless the DPA itself has issued a request for such a proposal.

Why this is bad: effectively, the DPA has created a “closed club” of weapons suppliers.

According to the current procurement procedure, the decision on whom the DPA sends a request for commercial proposals is made by a working group established within the Agency. This means that only manufacturers or suppliers selected by the Agency’s working group can submit commercial proposals (offer their products).

The procurement procedure, under the leadership of the DPA head Arsen Zhumadilov, does not specify the criteria—besides supplier verification—that the working group should follow. However, such working groups are usually formed to make questionable decisions and to shield members from criminal liability through collective decisions.

This same procurement procedure stipulates that the DPA will consider exclusively those commercial proposals that have been submitted in response to its own requests.

How it was before: any supplier could send a commercial proposal. Receiving a request from the Agency was only an additional opportunity to involve a wider range of suppliers.

Most importantly, to submit a proposal and thus participate in procurement, it was not necessary to be included in the decisions of the DPA working group.

As we mentioned earlier, the DPA used to inform potential suppliers about the submission of commercial proposals at key stages.

At that time, the procedure stated:

“All commercial proposals received, assigned an incoming number, and entered into the list of commercial proposals are subject to consideration.”

At the same time, the DPA immediately notified potential suppliers even about the fact of receiving their commercial proposals.

All commercial proposals must go through the DPA director, Arsen Zhumadilov.

Why this is bad: concentrating such a process in the hands of one person always creates significant corruption risks.

The new procurement procedure includes a clause stating that commercial proposals are also sent to the Agency’s deputy directors (program directors and DPA departments), but only after a resolution by Arsen Zhumadilov.

How it was before: as we mentioned earlier, the previous leadership followed the principle “everyone sees everything.” That is, all commercial proposals were immediately sent to the three deputy directors of the DPA, and only then forwarded to the relevant departments for execution.

Former Deputy Head of the DPA Artem Sytnyk said about the procedure for reviewing commercial proposals: “In 2024, all commercial proposals were immediately sent to the three deputy directors of the DPA: the Deputy Director for Development and Market Policy, the First Deputy Director, and the Deputy Director for Security. The procurement principle ‘everyone sees everything’ is an effective control tool and truly prevents even the thought of abuse. Under such conditions, no one can hide a commercial proposal from an ‘undesirable supplier’ in a desk drawer.”

“Commercial proposals that ‘get lost’ or are ‘hidden in a desk’ were the basis for typical schemes in the Ministry of Defense and the DPA during the tenure of the first head, Volodymyr Pikuzo, which explains the huge share of contracts awarded to intermediaries in 2023 and early 2024. For example, a commercial proposal arrives at the DPA from a manufacturer with a genuinely good price. Nothing happens to the proposal within the DPA because it ‘gets lost somewhere,’ while the information is leaked to the necessary intermediaries. After some time, these intermediaries approach the manufacturer and offer to buy the product at a higher price. Then the DPA purchases the same product but at an even higher price from the intermediary with insider information.”

Lack of publicly available terms and deadlines for supplier verification

Neither the previous nor the current management of the Agency managed to implement this change. However, it is critically important for effective work with weapons suppliers.

For example, if a new manufacturer or supplier has not previously worked with the DPA, they must undergo verification. How quickly this verification is completed determines whether the supplier will be able to participate in the Agency’s upcoming procurements.

However, clear deadlines—how long the verification process takes—and, most importantly, when the potential supplier will receive a response from the DPA have not been established. This is evident from the verification procedure and the recent amendments to it.

For businesses, this is critical. Without clear timelines, they cannot plan whether they will manage to complete verification in time to sell weapons and secure multi-billion contracts, or if it’s easier to sell on other markets.

The Agency’s website has a form for potential suppliers to undergo verification. There are no major issues with the form itself. However, clear deadlines for completing the verification (as well as the Agency’s official order on the verification procedure) are not publicly available for DPA suppliers. Additionally, the decision on verifying potential suppliers is made by a separate working group within the Agency.

Despite this lack of transparency, the Ministry of Defense regards the current verification rules as innovative.

“It [verification] helps ensure that the company meets basic requirements: it has no ties to Russia, Iran, or Belarus, and has sufficient production capacity and financial standing to fulfill contracts,” the Ministry of Defense explains.

The Ministry of Defense’s official communication also states: “After passing verification, a supplier is added to the registry, which reduces the time needed for future checks and enables prompt receipt of requests for commercial proposals from the Defense Procurement Agency. This will make procurements faster, more efficient, and more predictable for both parties.”

However, as noted above, such “more predictable” procurements may only be accessible to a narrow circle of suppliers who have already received a request from the Agency and successfully completed verification in a timely manner.

The changes introduced by Minister of Defense Rustem Umerov and the head of the Defense Procurement Agency, Arsen Zhumadilov, have undermined the previously clear and transparent rules governing defense procurements.

Instead of transparency and mutual oversight — which are critically important during wartime — we have received a “closed club” of suppliers. The decision whether to admit a proposal to the next stages of procurement is made unilaterally, manually, by the head of the Defense Procurement Agency.

Such decisions not only limit the participation of manufacturers in supplying the necessary armaments but also create the perfect breeding ground for abuses and corruption schemes. The established conditions mean that obtaining a state contract for arms supply is possible only through the “right connections,” rather than on the basis of the best price, quality, or delivery terms.

Against the backdrop of a full-scale war and resource shortages at the front, the current model creates risks not only for weakening the army’s combat capability but also for turning the procurement system into a tool for the misappropriation of billions in budget funds. And this happens at a time when every delay or overpayment costs us not only money but also human lives and irretrievably lost opportunities on the front line.